Horror Stories

The Terrifying Case of The Cleveland Torso Murders

During the 1930s, Cleveland, OH was a city on the rise. It rapidly began growing as a manufacturing hub, and with that brought laborers and workers into the city. The population boomed, but like all American cities at the time, the Great Depression caused many to lose their homes and their livelihoods. “Hoovervilles” or “Hobo Jungles,” makeshift shanty towns occupied by the so-called “working poor,” sprouted up in areas around the city. In particular, the lower income neighborhood of Kingsbury Run in the southeast side of Cleveland was a dark and dangerous area located just west of the Roaring Third, which became known for its bars, gambling dens, brothels, and vagrants. Despite its dangers, the people who lived here likely had nowhere else to go, and it’s this vulnerability that one horrific killer would easily take advantage of.

On September 5, 1934, an unidentified woman was found washed up on the shores of Lake Erie, or, at least some of her did. All that was found was the lower half of her torso with the thighs still attached but amputated at the knee. It was noted that some kind of chemical preservative was used on the woman’s body, leaving her skin red and leathery. Her head was never discovered and because of this she has never been identified. However, it would take another year until the case for a killer was established, and it would take two more until the woman, dubbed the “Lady of the Lake” was added to the investigation.

Just over a year later on September 23, 1935, the decapitated body of a man was found at the base of Jackass Hill in Kingsbury Run. He was naked and emasculated as well as being drained of all his blood. His head was found buried nearby and the victim was identified as Edward Andrasy, a 28 year old hospital orderly who was known to frequent the Roaring Third. On the very same day, a third victim was found nearby, a 40 year old man also decapitated and emasculated. His skin appeared to have been treated with the same chemicals as the first victim. Though his head was later recovered, the man was never identified.

In January of 1936, remains of a woman were found wrapped in newspaper and packed into half-bushel baskets left out in the open alongside the Hart Manufacturing building. Eventually, the whole body except for the head would be discovered, and the woman was later identified as Florence Polillo, a 43 year old sex worker and barmaid who lived right on the edge of the Roaring Third.

Later the same year, starting in June, three more bodies would be discovered: all men, all decapitated and dismembered. The first, dubbed the “Tattooed Man” presumably after the 6 tattoos found on the victim’s body, was found in front of the Nickel Plate Railroad police building. In spite of fingerprints and tattoos, he was never identified. Then, the next month, another body was found in the woods near Big Creek on the west side of Cleveland. The remains appeared to have been there for at least two months, and the large quantities of blood found at the scene led police to believe that he was killed there, as opposed to the other victims who had all been moved. Due to rapid decomposition the man was never identified. Later on in September, the upper half of a man’s torso was found near railway tracks that run through Kingsbury Run. The other half of the torso and legs were recovered, but the head was never found and the body was never identified. The coroner took special note of this victim because it appeared as if the head had been removed with one clean stroke.

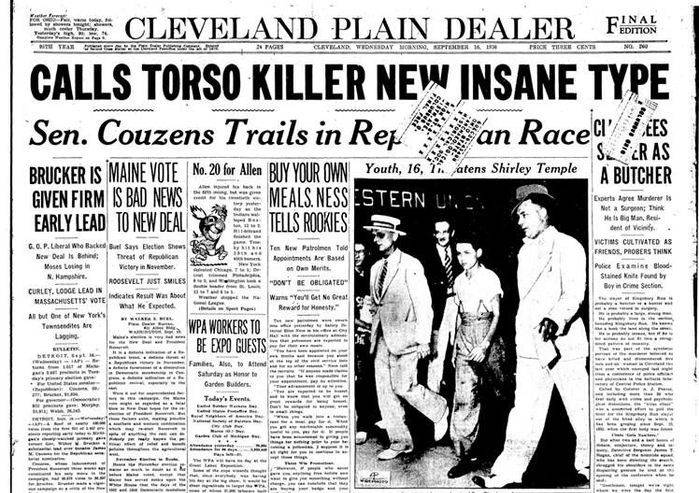

Six brutal murders in one year, and the Cleveland police had no leads or suspects. At the time, renowned lawman Eliot Ness of the Untouchables fame was working as Cleveland’s public safety director. According to a speech given in 1936, Ness reports having uncovered a police department rife with corruption that he vowed to stomp out. Indeed in the following years Ness worked to transfer and fire many officers in an attempt to clean up law enforcement. This change in structure was needed, but it could very well have contributed to the slow initial investigation into these killings. It’s quite possible that more veteran officers were let go while other less experienced ones gained power just because Ness liked them. We can’t know for sure, of course with the case being over 80 years old, but regardless, Ness and the police were certainly at a loss.

In February of 1937, the torso of a woman washed up on the shores east of Bratenahl in the same location as the Lady of the Lake. Her legs, arms, and head were never recovered, and the victim was never identified. Later that year in June a boy discovered a human skull under the Lorain-Carnegie bridge. Next to it was a burlap sack that contained more skeletal remains of what appeared to be a 40 year old black woman. Investigators found distinct dental work on the victim, and because of this many believe her to have been Rose Wallace, though the identification has never been confirmed. The next month the dismembered body of a man was found floating the Cuyahoga River. The whole body was eventually recovered, save for the head, heart and internal organs, the last of which appeared to have been ripped from the victim’s body. The victim was in his mid-30s and was never identified.

The following year, in April of 1938, the lower half of a woman’s leg was found on the bank of the Cuyahoga River. In May a thigh was found floating in the water nearby, and an investigation resulted in discovering the torso and another thigh in burlap sacks under a nearby bridge. The rest of the body was never found and the woman was never identified.

The last two known victims of the Torso Killer were discovered on August 16, 1938 in a landfill on the east side. The first was the headless torso of a woman wrapped in a men’s blazer and then again in an old quilt. Her legs and arms were found wrapped in butcher paper in a makeshift box nearby. A few yards away, police discovered a second body, that of a dismembered man. Both bodies were placed in plain view of Eliot Ness’s office window with the probable intention of taunting him. This seemed to work in riling Ness up, as only two days later he deployed a group of thirty-five police officers and detectives to raid the shanty town of Kingsbury Run. Police apprehended sixty-three men in connection with the killing and later went back to search for more clues. On Director Ness’s order, the shanty town of Kingsbury Run was burned to the ground. All of the people displaced from their homes were then arrested for vagrancy. Ness’s defense for this was allegedly to collect fingerprints to identify new victims and to push potential victims out of the killer’s hunting ground, but his actions were largely criticized and ultimately would not lead to any breaks in the case. However, for whatever reason, the killings would stop after Ness’s commands, but whether his draconian orders were the cause is highly debatable.

During the time of the investigation, authorities interrogated over 9,000 people in relation to the case, making it the largest police investigation in Cleveland history. One of the main investigators, Peter Merylo, believed the Torso Killings were connected with a series of similar murders near New Castle, PA, and because of this believed that the killer may have been a transient who rode the rails that directly connected the two cities. Merylo went undercover as a homeless person and rode the train route numerous times in an effort to find the killer but was never successful.

In August of 1939, a man named Frank Dolezal was arrested in connection to Florence Polillo’s death, as he at one point lived with Polillo and also had connections to Edward Andrasy and Rose Wallace. Dolezal was heavily interrogated by police to gain a confession. The “confession” he would wind up giving was largely incoherent and rambling with Dolezal missing key details, leading to many believing he was coached. Just before the case could go to trial, however, Dolezal was found dead in his cell under suspicious circumstances. Dolezal had somehow managed to hang himself from a hook placed five feet and seven inches off the ground, despite standing at 5’8” tall, along with six broken ribs. He would eventually be posthumously exonerated on any involvement in the Torso Killings.

The other main suspect identified by investigators was a man named Francis Sweeney. A veteran of WWI, Sweeney had medical experience performing field amputations. After the war he became an alcoholic to deal with the shell shock and nerve damage he received from being gassed. He operated an unmarked doctor’s clinic located right next to a coroner, where it is believed he could have practiced and taken his victims for a cleaner and easier kill. He would be interviewed by Ness himself in connection to the Torso Killings, but when he was first arrested he was allegedly so inebriated that they left him to sober up in a hotel room for three days. During the interrogation, Sweeney was given two polygraph tests administered by co-creator of the machine Leonarde Keener, which he failed both of. Keener is said to have told Ness “that’s your man.” Unfortunately, all the evidence they had on Sweeney was circumstantial, and the fact that he was the cousin of one of Ness’s political opponents, Congressman Martin Sweeney, led Ness to conclude that there was very little prospect in obtaining a successful prosecution. Just days after Sweeney was released by the Cleveland police, the last two victims would be found near Ness’s office window. Ness also believed that Sweeney continued to send him mocking postcards well into the 1950s which only stopped after Sweeney’s death.

Nearly 90 years since the end of these killings, we still don’t know why they were committed, or who did it. It remains one of Ohio’s most perplexing and certainly frustrating cases. The depravity of the Mad Butcher and his gruesome methods of dismembering his victims would make him an infamous figure in true crime history, but unfortunately this case is seldom talked about even within true crime communities. A more prolific and gruesome killer than even Jack the Ripper, but he has almost entirely been lost to time, and most tragically, so have the majority of his victims. Eliot Ness believed he knew who the killer was, but was unable to take any meaningful action against him, taking the identity of the killer with him to his grave.