Editorials

An Immersive Cult Indoctrination Experience: What Makes ‘Midsommar’ Stand Out Even Today

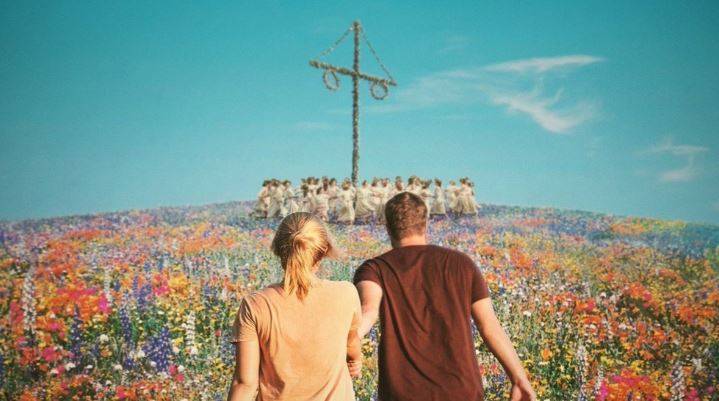

What’s done in dark comes to light quite literally in Ari Aster’s film Midsommar, but don’t let it blind you; there’s more than meets the eye in this visually stunning masterpiece, and the deception within is exactly why the film is still being dissected 4 years later.

Incredible cinematography, acting, and shock value aside; There’s one major ingredient that makes Midsommar a unique and spine-chilling dish, and you may have just missed it. While you begin the film as a spectator, by the end you’re the main character — your reaction is a test.

Emotions run high for the entirety of the film, blindsiding viewers to its true intentions in order to mimic commonly used brainwashing methods. When you’ve seen the lowest of low, endured trauma and heartache; comfort can be found in even the darkest places… Especially in broad daylight surrounded by trained manipulators.

Watching the dull and familiar scenery transform into a kaleidoscope of color, feeling the sense of being alone and misplaced in a room full of peers wading off as you enter a group that is seemingly welcoming and unabashedly loving; these are intentional tools of comparison used to rationalize brutal cruelty and strangeness within the new community.

The main antagonist, Pelle (Vilhelm Blomgren) introduces Dani (Florence Pugh), her emotionally absent boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor), and his group of equally-distant-to-Dani friends to The Hårga in Halsingland, Sweden where he grew up. Pelle is fully aware of the tragedy which befell Dani of losing her family to a murder-suicide, and the rocky relationship she shares with Christian.

At first glance, Pelle appears to be the most compassionate of the bunch: regularly checking in on Dani’s wellbeing and, of course, the confusingly intimate line: “…Do you feel held by him? Does he feel like home to you?”. Directly following a ritual in which two Hårga elders commit suicide in front of everyone, this confusion is shared by character and viewer alike, both clearly drowning in the events which have transpired — yet moved by the sentiment in contrast.

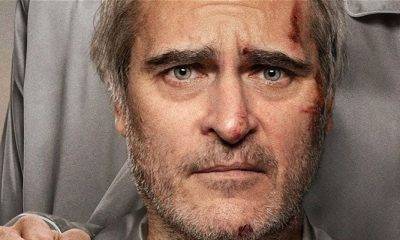

Pelle with Dani – Midsommar

Once again, this is an intentional choice for both director and the cult made to prey on the newly vulnerable. How validating it is for the viewer to witness a shred of empathy toward Dani’s experiences after nothing but empty gestures from everyone around her makes the deliberate action of allowing her to be re-exposed to the trauma of death almost entirely forgotten.

This is mirrored throughout their entire experience in and out of Halsingland, Pelle fully aware that her reoccurring sense of absolute desolation would soon be met with overbearing amounts of love and acceptance.

That warm glow you felt the first time you basked in Dani’s final smile was misplaced. On the surface, it seems the beloved and broken protagonist has finally found what she’s been sorely lacking: community, empathy, and true connection. Especially after witnessing the many gut-wrenching scenes in which she stifles her cries of pain in isolation compared to the sweet release of agony with a group of women sharing in, what appears to be, incomparable compassion.

But make no mistake, the duality of these scenes is nothing short of intentional, as are the actions of members of the cult in which Dani has found her “home”.

Played out on-screen, but also within your own mind and emotions, Midsommar brings a new twist to immersive experiences and poses a question to its audience of which the answer lies in their perspective of the events that transpire: Could you be indoctrinated into a murderous cult?

With the overwhelming amount of us who felt joy as the credits rolled, it’s safe to say that we’re all a bit more susceptible than we’d hoped, and no horror movie has yet to make us question our own minds in quite the same way.