Editorials

Incised Wounds of Holiday Horror

Find out what horror to watch during these holidays with this new list!

This time of year always feels like a dark procession, as if we are celebrating everything we’ve sentenced to end. For some this feels inevitable; for others, it’s a world wrestling with its last thread of decency. Though the films on this list are not typical odes to holiday horror, they are pivotal ones. This is how we worship violence as a cyclical melody; the incised wounds of holiday horror.

Icicles as Knives: The Cosign of Nature & Death by Nurture

The Shining [1980]

This depiction of a fractured mind is contagious. It is a fixed portrait of how nature can nurture the worst parts of us– and magnifies them for a greater purpose. The audience wanders through a maze of ill-fated coping mechanisms. From alcohol abuse to domestic violence, we underestimate the power structures [+landscapes] have to change our core responses, beliefs, and intentions. The pressure of expectation plays like an abstract. In the end, nature takes what it wants and disregards the rest.

The Invisible Man [1933]

The Invisible Man can best be described as the original deep dive into the human condition, to the innate brutality we all agree to support. A ‘mad’ scientist stages his suicide as a pre-game for hunting his ex-girlfriend. He uses scientific tactics to become invisible and avoid consequences–an appearance of gaslighting before it had a name. It’s a dedication to wreak havoc, to holding up the mirror to bystanders and their selective involvement. Our society casts victims as villains, as architects of their demise, and then we ask why they stay. This film unearths all the bodies we’ve buried and the lives we traded to compartmentalize. This is about an existence sustained by our silence, blame, and addiction to superiority. The audience is given a menacing guideline; It asks them to take responsibility for their day-to-day actions to preserve the agony.

Christmas as The Noose: Consumption as Family Violence

Hostage [2015]

Hostage is a fever pitch in familial violence. During the holiday season, a teenage girl learns the truth about her past, her parents, and the chaos that made her. The audience is asked to suspend expectations by challenging how, when, and where society identifies its victims. Hostage presents an inverted home invasion narrative that spotlights consumer culture and plays on our instinctual fear that no one is who they say they are.

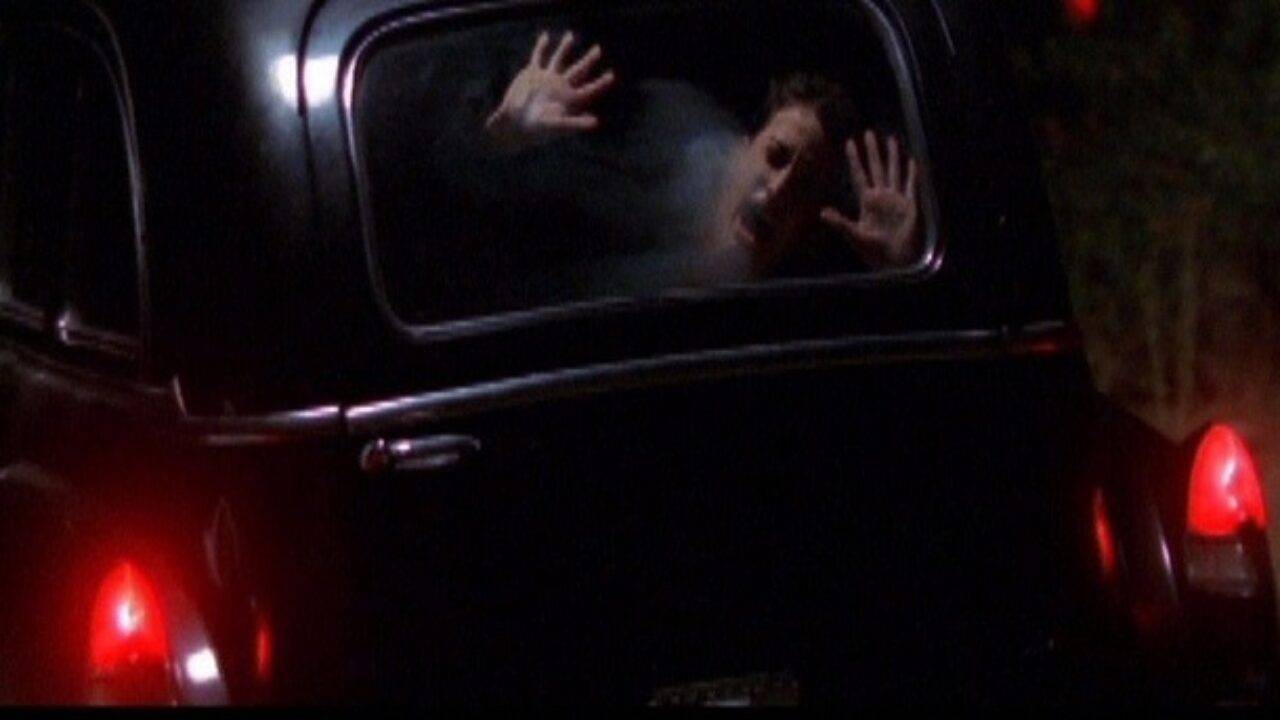

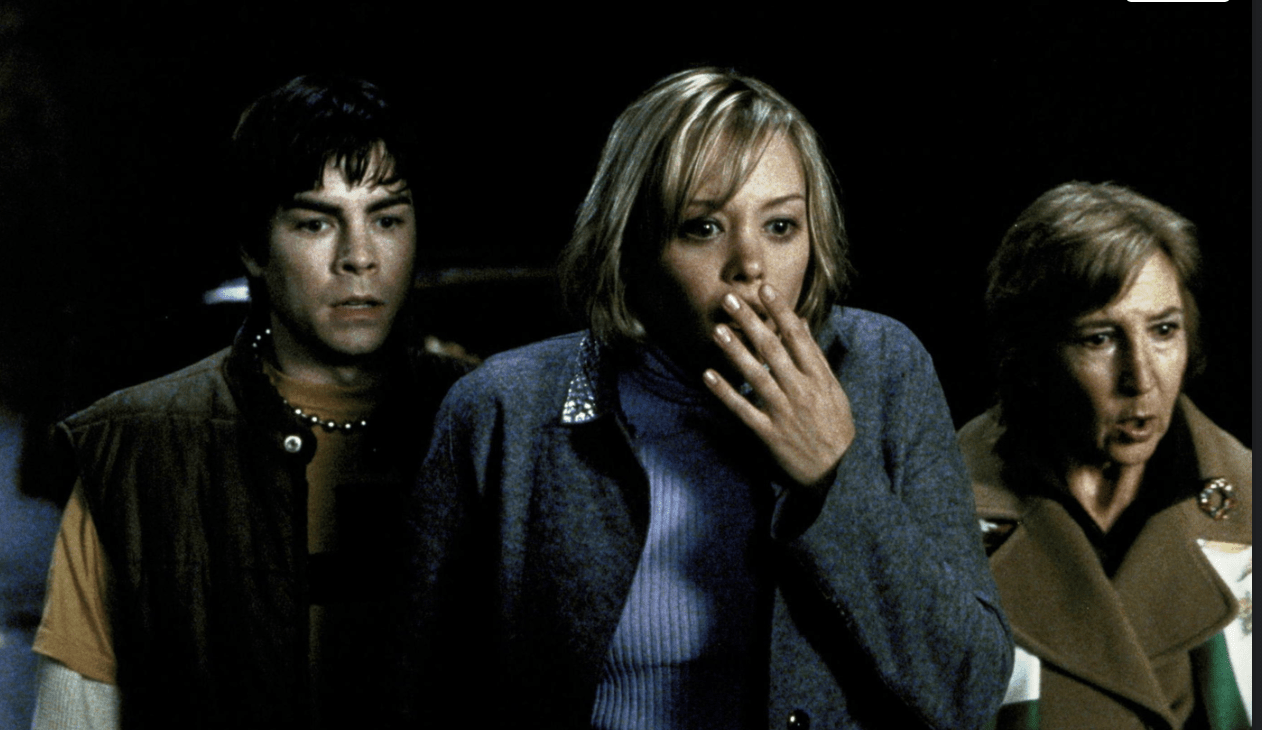

Dead End [2003]

On a Christmas road trip, a family becomes locked in a nightmare that manifests as all their worst fears. The car is a standard congregation site; it’s also a trap. To be strapped into a torture chamber going 70MP is the real threat. You can’t walk away, you can’t avoid, and you’re forced to get all your hearts on the same beat. With its dream-like quality, Dead End drafts portals to another world where seconds turn into hours. As things begin to unravel, the plot strikes a chord with parts of us that we wish wear us away. Dead end captures the flash of light between your pain in this world and your begging in the next.

Larceny + Mistletoe: The Price of Violent Belongings

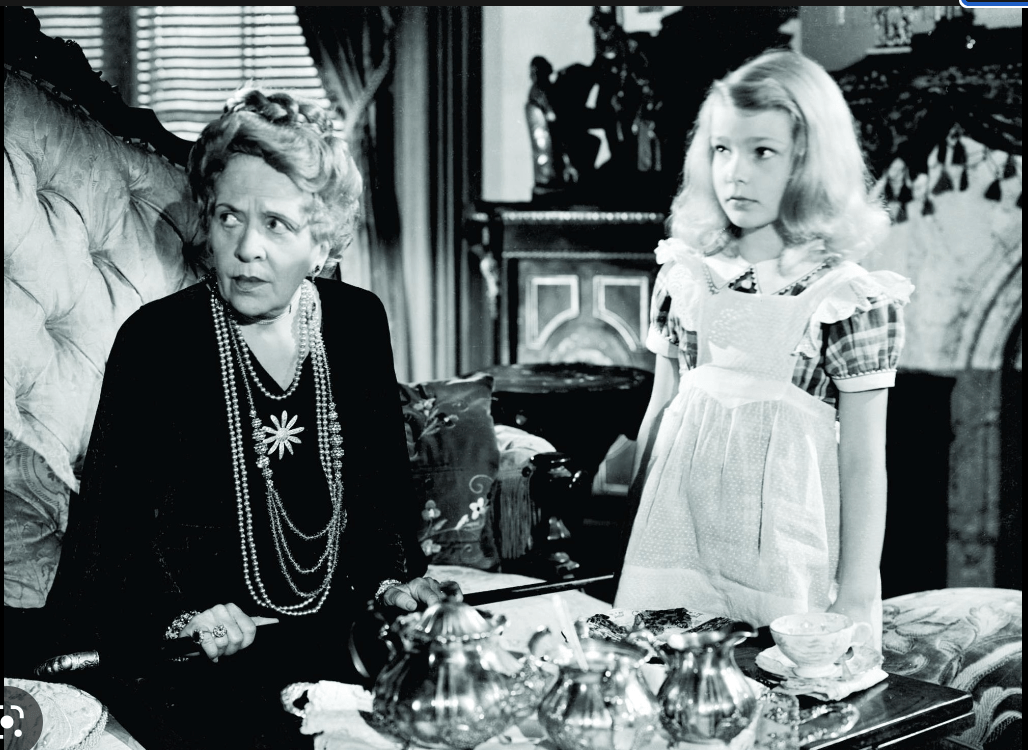

Curse of The Cat People [1944]

Curse of the Cat People is about the aftermath of pregnancy and marriage, a universe dominated by trauma, secrecy, and submission. The audience experiences a crash course in this mind-bending lore of women’s sexuality and what can be destroyed in its wake. Staged as a prolific warning, we are subjected to the lingering effect of what we are commanded to do and what we’re willing to do. The lesson will repeat as needed, and the mother’s sins will echo in the child.

And All Through The House [1972 + 1989]

Tales From The Crypt is home to the most iconic Christmas horror vignette in history, And All Through The House. It’s a diorama of the American family. On the surface, it’s a tale about a greedy wife who kills her husband on Christmas eve. Typical of the horror genre, this story arrests our perception of villain and victim– suggesting both can occupy the same dwelling and both will lead us to the end of the earth.

Tidings of Comfort & Joy: Congregation as Impenetrable Violence

The Children [1980]

Few films in cinema history dare to capture the controversy of child killers with the same ingenuity. The film has a texture; you can feel the weight of the choice between being harmed or harming your assailant in self-defense. It’s a cultural obsession to believe in children as they are depicted in fairy tales but never our worst nightmares. It begs us to consider our role in a child’s temperament, in their response to the world. We’d rather die at our children’s hands to avoid any admission of wielding the knife.

Body [2015]

After ‘breaking’ into the home of a former employer over the holiday break, three friends participate in a series of poor choices- leading to a battle of wills and fleeting accountability. We are forced into a sickening reality. l Though the girls appear just like anyone else, moments of pressure expose how quickly our morals can give way to the ego and need to be validated by fitting in.

Let There Be Suppression: Accountability By Way of Terror

Us [2019]

Us is a cinematic resource that makes use of absolute world devastation. It takes our accountability to the front of the line. Us defines the relationship between the haves/have-nots as a society that performs kindness with narcissistic avoidance. We will do anything to misdirect the grief. No one wants to acknowledge their part in orchestrating other people’s pain. After all, It’s a revolutionary thought to reflect on yourself, and the US is sufficient evidence. The message is heavy; a reminder that status and hierarchy can cloud our conscience, for whatever we attempt to bury will return until one of us dies.

Holiday Horror feeds avoidance; and builds augmented reality. In a split second, we’re expected to give every dark thought a rest but never cope with the seasonal atrocities that frame our addiction to the light.

Check out more editorials here or visit The Horror Advocate to learn more about me and my work